Your Sonar is a Toy

Ok, the title is a bit provocative, but I’m often asked why our side scan sonar process is any different from others. Lots of recent model fishfinders from Garmin, Lowrance, Humminbird and other consumer companies have side scan features. For a few extra bucks, you can even get nifty gadgets like “live scan”. And most boats from law enforcement agencies and first responders have these units built in. So what’s the problem? Lots of problems.

Searching In the Dark: Dark, Black Water

Here’s one. If you’re a fan of detective shows, maybe you’ve heard of the “streetlight effect”. The "streetlight effect," also known as the "drunkard's search principle," means you only look where the light is shining, right under the streetlamp. It’s too hard to look anywhere else.

That’s an apt analogy for how side scan sonar works! It’s sending sound waves down at about a 10 degree angle from the water’s surface, measuring the reflection or return, and translating that into an image, for visual consumption by a human brain. That’s the streetlamp! It’s lighting up stuff along the sides of the boat as it cruises along. And… you can’t see anything else.

But maybe you’ve seen some of the demo screens. They’re really quite impressive. In this example, you can see a lot of detail on this submerged bridge. Amazing, right?

Look a little closer, though, and you’ll see that the depth is less than 20 feet. And that’s a huge bridge. It’s right under the streetlamp, so it’s not really surprising that you’d see the bridge in vivid resolution.

Angles Matter

Consumer sonar units work like this, sending signals toward the bottom from a transducer mounted on the transom of the boat.

The side scan signal goes out at an angle of around 10 degrees below the water to the left and the right. That means there’s some area right under the boat that the sonar can’t see, and the sweet spot where the image is best is farther away the deeper the water gets.

So if you’re in 10 or 12 feet deep water, you’ll see the bottom pretty clearly. The streetlamp is right next to you. If I were to represent this as a stick figure walking along trying to find someone, they’d look like this:

I would almost certainly find the person I was looking for. They’re right under the streetlamp! Or they’re not there. But what happens if I’m in deeper water?

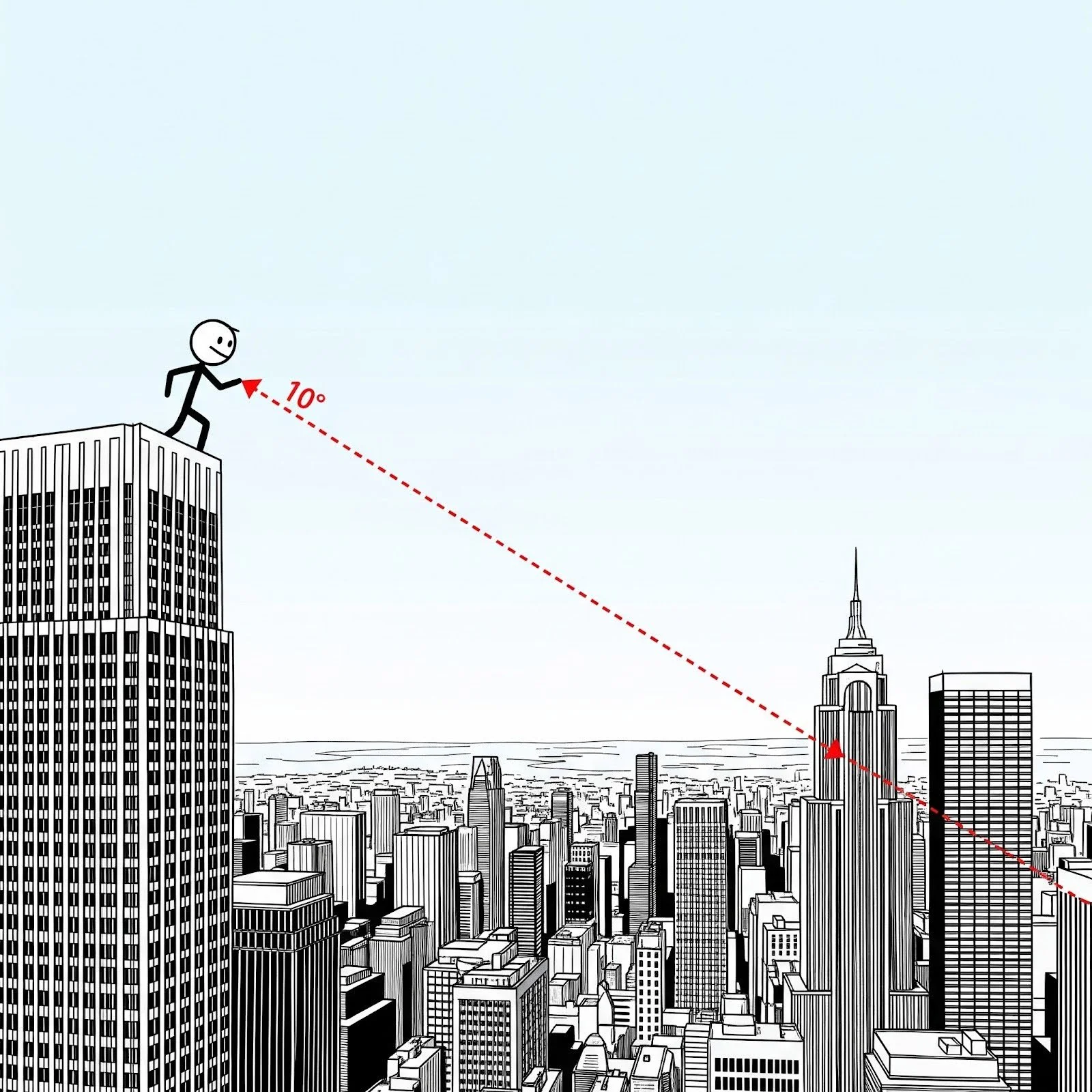

That’s more like me being atop a building and looking down at that same angle. It looks like this:

Now I’ve got a problem! Anything I see is really far away, and I probably can’t tell one person from another, even if I can make out buildings and trucks. A person would be really tiny. And what about all the stuff on the street below me? It’s completely invisible!

Controlling The Heavy Sonar So It Can Fly With Precision

And that’s the first big problem. We can fix this by moving the transducer deeper in the water. Since we can’t sink the boat, we use a towfish mounted on an adjustable cable that can fly along 10’ above the bottom.

This unit is heavy, since it has to sink, and needs to stay down as the boat pulls it along, and that generally also requires a power winch to raise and lower the unit to keep it at a steady altitude above the bottom of the lake or bay. There’s also some management of all that machinery as the boat moves along flying the towfish, sort of like an upside-down kite.

These more industrial units are connected to computers that record the sonar data so we can review it any time. It’s sometimes the case that we don’t find our person until we’re reviewing the search on a big screen later. That data includes a GPS location and time stamp so we can go back to the precise location and investigate anything that looks promising.

The software included as part of these systems also includes tools to measure items we might see so we can verify the size of possible search targets. Recording and measurement are not a part of consumer level units, and require more training, experience, and ongoing practice to use properly.

Closing the Gap: Sweeping with Rigor

Now that we can actually look on the bottom, and we can review and analyze things we find there, we still need to find our victim. That means we need to be able to know what areas we have searched and what areas we haven’t yet searched.

With that Garmin or Lowrance device, you’re basically just wandering around. There’s no guidance to help you know what areas your scans covered, and what’s not yet covered. And since you can’t record anything, maybe it doesn’t matter. "Drunkard's search principle," indeed!

To cover an area thoroughly, we use software (we developed it) that guides us through a process we call “mowing the lawn”. We can see visually what has been covered, and what remains. We’ve also created tools that help us keep our search grid lines reasonably straight, and with good overlap, even in current and wind.

Overcoming the “Streetlight Effect”

With the navigation tool, we can separate the roles of navigating the boat to cover the entire area methodically, and managing the sonar apparatus to get the best possible view of the bottom and look for promising search targets. It requires a team effort with coordinated tools.

A well executed search with a solid point-last-seen generally results in a recovery. But it takes the right tools and constant practice.

Without the right sonar tool, you’d better be in shallow water. Without good measurement and recording tools, you’re making a lot of on-the-fly judgements. And without good navigation tools, you’re really just wandering around. So, maybe your side scan sonar system really is a toy. Sorry.

Recommended resources:

Excellent series on side scan sonar use from an industry veteran: https://www.youtube.com/c/SonarTechSkills