Side scan SONAR searches

When a search truly covers a large area, the best tool available is usually a technology known as side scan sonar. Like other underwater search modalities, this technique hinges on an accurate point-last-seen, but it’s tremendously effective in large areas, where the point-last-seen is somewhat hazy, or the water is deep enough that divers can’t spend enough time underwater to search effectively.

When people see us working, they often ask what the industrial-looking winch mounted on our boat is all about. This is part of an overall system that includes a sonar towfish, long cables, and a computer system.

The sonar towfish is a device that looks a bit like a torpedo, and it’s attached to a computer system via a long cable that transmits data about the seafloor or lake bottom we’re searching.

This sonar data generates an image of the bottom beneath the boat by sending soundwaves to the side (hence “side scan”), and analyzing the echo. It’s a bit like shining a flashlight across the floor in a misty room - we don’t get super clear images, but we do get a good sense of what’s on the bottom: rocks, logs, trees, and hopefully, our search target, generally a drowning victim.

The overall system can be a bit of a mess, but when we have it installed and working, it’s a very effective tool

Towfish sonar is mostly used in industrial settings, to make maps of the seafloor. It’s great for finding ships, examining piers and bridge structures, and getting a better understanding of the underwater terrain. Our systems are generally older systems that some agency upgraded.

In concept, this sytem is similar to a feature found on some modern fishfinders. There are big differences, however.

A fishfinder side-scan relies on sending sonar signals from the transom of the boat, so it’s great in really shallow water, or looking at schools of fish. At depth, it’s useless. A towfish system is needed.

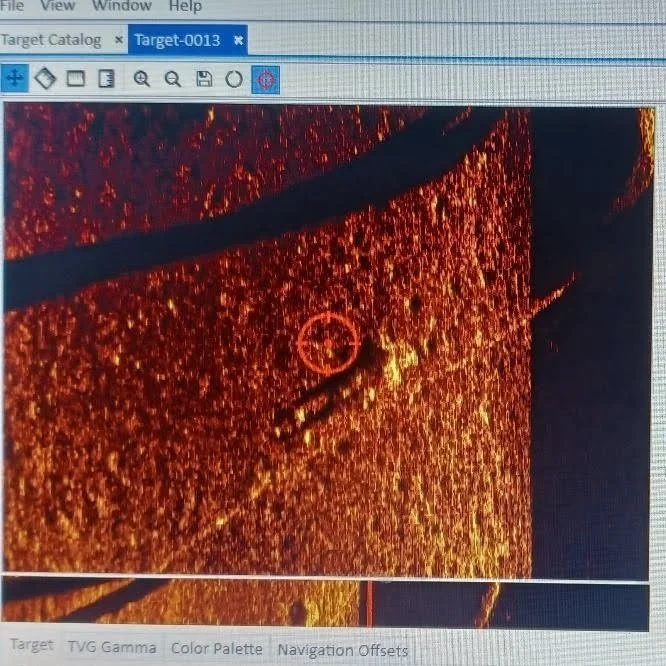

Image of sunken small boat

As we tow the sonar unit through the water, it creates a screen that looks like this image. The towfish flies through the water about 10 feet above the bottom, and sends sound waves to the side. The dark area in the middle is the area direcly below the towfish, a blind spot. As we traverse through our search area, we’re generating an image map of what the bottom terrain looks like, and we’re closely examining objects that merit further attention.

One of the important tools in this system lets us measure items on the screen. If we’re looking for a person, and that “thing” is 12 feet long, it’s probably a log. That thing on the left hand side of the screen above? It’s about 15’ long. Definitely a small boat. Our system computers also record the search imagery as it goes by, so we can review it to make sure we didn’t miss anything. As we’ve noted before, it’s also important to eliminate areas that have been searched thoroughly.

When we’re searching underwater with a sonar system, we use a methodical process that we call “mowing the lawn”. Like the description, we’re towing the sonar back and forth in an expanding pattern across the most likely area searching for our target. This process ensures complete coverage

Sonar data can look different, depending on the angle of the sound waves, and there’s always the dead zone you can see in the image above, so we try to make sure we double-cover the entire area. The map shown here is an aerial view of one search pattern, where the white line is the track of the boat, and the pink area is the sonar coverage on the left of the boat, blue on the right side of the boat.

The sonar imagery can extend 50-75 feet on either side of the boat with good coverage for small objects, so we can cover a very large area in a small amount of time. In this particular search, we found our target shortly after starting, and did an additional scan at an angle to make sure we saw it clearly from an alternate angle.

Because this is a specialized process, we created custom tablet software tools to guide us through search navigation. Boats are subject to movement from wind and current, so “mowing the lawn” can be tough. We need complete coverage, without gaps, and with good sonar images. Choppy water, lots of underwater debris, changing depths… Sometimes we need multiple passes to be sure.

In this map, we searched a pier in the San Francisco Bay, and some of the challenges were “seeing” under the pier and dealing with a significant tidal current.

Our tablet software, together with the software included as a part of the sonar system, ensures that we’ve covered things thoroughly: either we find our victim, or feel pretty certain they’re not in our search area.

In this search, you can see the tight overlapping nature of the sonar coverage. You can also get a sense of the amount of territory we covered in an hour or two.

Another unspoken advantage of this type of search is that it reserves diver hand searches until the very end, if at all. Diving always carries some dangers, and some of our sonar searches are in water well over 200 feet deep - too deep for dive operations.

When we locate our victim, the image is often stark. The victim stands out from the lake bottom, and we’re able to confirm with measuring tools.

Our recording software captures GPS locations so we can navigate back to the exact location and place a marker to make a recovery. Our search has narrowed to a new point-last-seen that is only a few feet from the victim. Our divers will be able to make a recovery with a minimum of time spent underwater.

Used properly, side scan sonar is one of the most powerful tools available in the search for drowning victims. The technology can be complicated and expensive, but it is a game changer in the underwater recovery process.